Why did you decide to undertake this project? What was it designed to achieve?

After a whole-school learning and teaching review, praise was identified as an area for development for the whole school and it seemed important to identify answers to the following questions:

- What does praise look, sound and feel like?

- How do students feel about their experience of praise within school?

- Most importantly, how can we harness praise to have the biggest impact on student motivation?

Research summary

Praising effort can be problematic.

Many teachers are familiar with Dweck’s Growth Mindset theory, which encourages us to praise students for the effort they put in rather than the work they produce. It is believed that this makes students more likely to recognise their successes as a result of hard work, not natural ability (Dweck, 2007). However, this approach can be problematic if students have not genuinely put in good effort and in fact, if students believe they did not put effort in or if they did try but they ultimately failed at the task, then praising effort can lead the students to believe that the teacher has low expectations of both the effort and ability of that student (Willingham, 2006).

For praise to affect students’ motivation, it needs to be unexpected, spontaneous and genuine.

Students are cannily aware when teachers offer praise simply to motivate or encourage them and they often disregard it as a result. In order for students to feel that the praise is real, it must be given in a way that makes it seem like a spontaneous reaction to the work they have produced. This can be a challenge when working with large classes, but some suggestions for this are provided later. (Willingham, 2006; Center on Education Policy, 2012)

Positive praise has a more positive impact on motivation when it is given without suggestions for improvement.

A common approach to giving students feedback is the ‘What Went Well’ and ‘Even Better If’ approach in which students receive praise, closely followed by suggestions for improvement or targets. However, research suggests that students are often aware of this gentle manipulation and they are likely to disregard the praise and only focus on the suggestion for improvement, which many will take as a criticism. As a result, neither the praise nor the suggestion are as effective for students’ motivation as they could be (Didau and Rose, 2016).

Rewards should be unpredictable and for more exceptional work.

It can sometimes be tempting for teachers to praise students simply for completing a task in a timely way but research shows that this is likely to impact motivation negatively: no student needs to be praised for doing something they should be expected to do anyway. Similarly, if rewards become predictable then the positive behaviour that students display becomes associated with the reward and therefore students are less likely to complete tasks for the sake of the task itself (Lepper, Greene and Nisbett, 1973).

Research from the US Centre on Education Policy shows that motivation ultimately has a positive impact on attainment: ‘If students aren’t motivated, it is difficult, if not impossible, to improve their academic achievement, no matter how good the teacher, curriculum or school is’ (Centre on Education Policy, 2012).

Review of practice within school

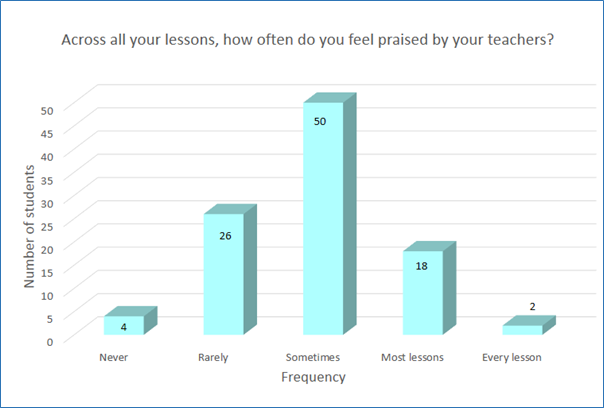

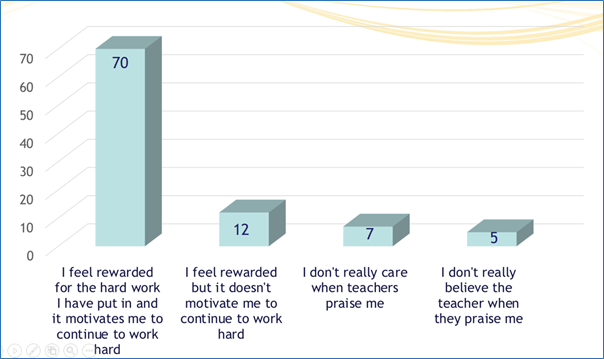

A survey was sent to a sample of students in order to identify what patterns of praise were currently occurring within school and how students perceive it. As the figures below show, the results suggested that there was indeed room for improvement, both in terms of the amount of praise given by teachers and the type of praise received so that it becomes more specific, in line with the findings from the research review.

The final graph shows the reason why these changes would be beneficial: students themselves agree that receiving praise motivates them to work hard.

Figure 1 “How often do you feel praised by your teachers?”

Figure 2 “What kind of feedback do you receive from teachers?”

Figure 3 “How do you feel when you receive praise?”

What impact has your project had on learning and teaching or outcomes in the school?

Three areas for development were identified that would enable the school to improve its approach to praise and have a greater impact on student motivation:

- Spontaneous/Meaningful Praise

- Uncoupling Praise from feedback

- Student rewards beyond verbal praise

In the following section are a range of suggestions for lesson activities and systems that would enable teachers to harness praise to increase student motivation. Many of them are not major changes to current practice but are instead designed to be reminders and suggestions for how to make more of praise within lessons.

Spontaneous or meaningful praise

As outlined above, research suggests that praise has the most impact if students feel that it is a genuine reaction to good work they have produced and that it feels meaningful. It is possible to achieve this aim by making minor changes to current practices used for praising students.

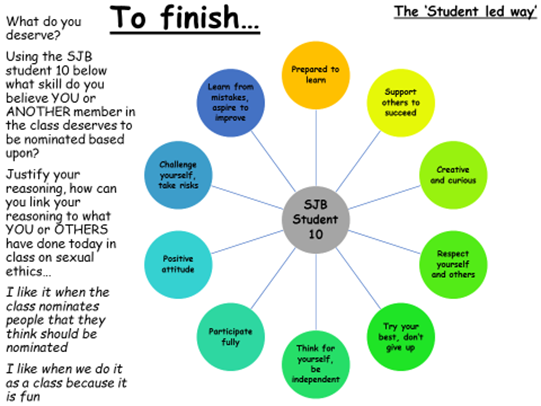

SJB 10

Our school’s central system for praising students is to ‘nominate’ students who have demonstrated behaviour that fits within one of the 10 areas of skills that students are encouraged to have, known as the ‘SJB 10’. Once students receive a certain number of nominations for each badge they are given a smart metal badge to wear on their blazer to show their achievement, and many students aspire to receive 10 badges across the school year. This is a system that has been in place for several years, but teachers are not consistent in how they use it and often nominate students without letting them know about it.

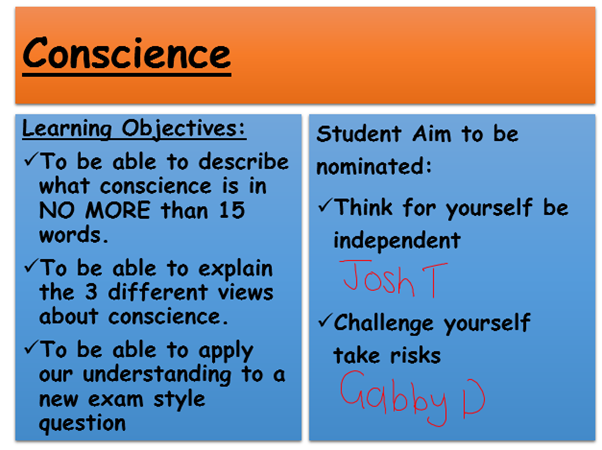

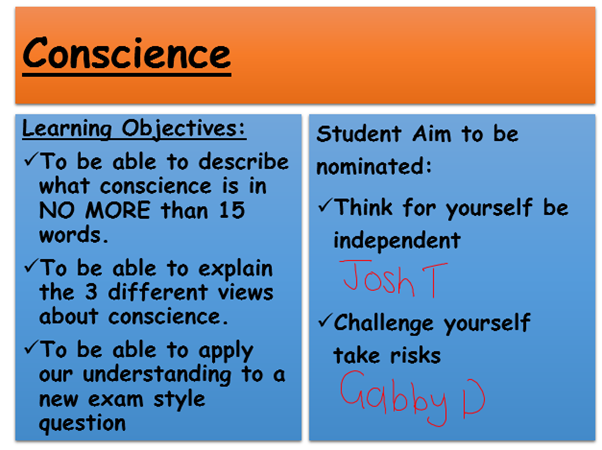

A number of teachers trialled changing their approach to nominations so that students are made aware of which aspects of the SJB 10 were being targeted in each lesson and then using their plenary to decide (either as the teacher, or collectively as the class) who should receive the nomination for each aspect.

Figure 4 An RE lesson slide, showing the information given to students at the start of the lesson, which was then revisited at the end with the nominated students added

Figure 5 A photo of the whiteboard in a DT lesson in which students first discussed how each learning skill would look in practice. At the end of the lesson, the teacher put forward potential students who could be nominated and then decided on the final selection.

A variation on this theme is to ask students to nominate themselves and then have the teacher decide who is the most convincing.

Figure 6 Plenary slide from a Business lesson in which students suggest why they deserve a nomination, or reflect on why they do not deserve a nomination

Although this method could be successful for some classes, the teacher who trialled this found that it was often only the more confident students who put themselves forward, so teachers should be careful when choosing which classes to use this approach with.

An alternative is to ask students to nominate each other, which can lead to greater reflection on what it takes to exhibit the required skill as well as encouraging meta-cognitive thinking. This can be effective in teaching children to self-assess their own learning skills.

Figure 7 A slide from an RE lesson in which students nominated either themselves or someone else in their class. They needed to justify their decision in relation to the topic of the lesson.

As with the above approach, this had varying levels of success and could of course lead to students only nominating their friends, but if students became used to the system it could be a valuable way of students reflecting on their own and others’ learning skills as routine.

Feedback from students

- “I love to receive a nomination in class because it makes me feel praised by everyone and a talented individual.”

- “I like receiving nominations from the teacher because I like to know they think I’ve worked well.”

- “I prefer when the teacher chooses who to nominate because people might be biased with their votes e.g vote for their friends. But it would be nice if the person would get told when they have received one.”

- “I don’t like having to put myself forward for a nomination – it doesn’t feel right.”

Give specific verbal feedback to a response rather than ‘Good’ or ‘Perfect.’

This is an obvious answer for many teachers but hopefully a useful reminder that we need to ensure that our verbal praise is as specific as possible. Here are some suggestions for how you can make your praise more specific:

- ‘That’s right’ or ‘Correct’ (a statement, rather than praise)

- Well done, that was a thoughtful/well-explained/creative/ detailed answer

- I really like how you…

- Your reasoning/strategy/ lateral thinking is impressive!

- That answer was A level/grade 9 standard because…

Uncoupling praise from feedback

As research suggests that students are less likely to respond to positive feedback if it comes alongside suggestions for improvement, it is important to try to separate the two steps to feedback. This could be achieved through teachers’ own marking by delivering the feedback in different ways. Positive feedback could be written in the form of a positive comment at the end of the work, while ‘even better ifs’ could be given using a code that students have to look up, for example.

This can also be achieved through peer feedback by having students peer assess in groups of three instead of pairs. This means that a piece of work is marked by two students: the first student notes only the positive things about the piece of work, the second student only writes the suggestions for improvement.

When trialled, this received a positive response from students. 79% of students asked agreed that they felt the positive feedback had been more thought-through by their peer assessor, while 92% said they would prefer to switch to this way of receiving feedback. Another benefit of this method is that students are able to read more than one person’s work and so are more likely to learn from each other in a way that will benefit their own learning.

There are of course issues of time and this method won’t always be appropriate, but it is something that teachers can try without the need for any extra planning.

Feedback from students

- “The positive feedback felt more genuine and thought through than it normally does.”

- “It makes me think carefully about the differences in what I did well and what I could improve.”

- “It was better than the way we normally mark, which is more focused on targets.”

Student praise beyond verbal rewards

Many teachers have their own system of praise or rewards within their lessons: prizes such as sweets or stickers, names on the board, raffle tickets awarded to students, postcards home or certificates naming them ‘Historian of the fortnight’ or similar. Since research suggests that rewards such as this can become meaningless if they become too regular, we tried changing the system so that students only receive the reward if they have done something particularly impressive. This trial was carried out using a raffle ticket system of praise and rewards

Using raffle tickets for praise

In a classroom raffle ticket system, students are given a raffle ticket if they do something that the teacher deems worthy of praise: an impressive verbal answer, working particularly hard, getting onto a challenge task, or getting a good score in AFL. The student writes their name on the back of the ticket and, at the end of the lesson, puts it into a pot. The teacher then draws out a name at regular intervals (once a week, fortnight or month) and that person wins a prize. This prize could be sweets or chocolate but could also be the offer of a postcard or phone call home, which is particularly popular with many students.

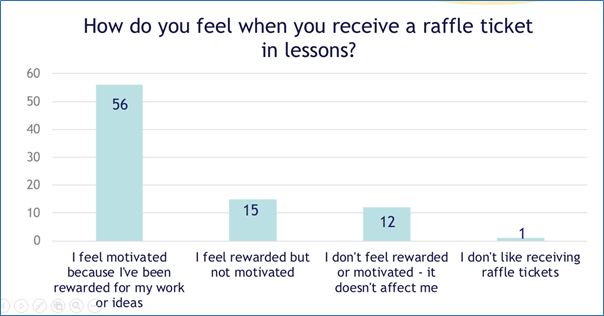

Feedback from students from this method of praise is largely positive:

Figure 8 graph showing student responses to a survey question

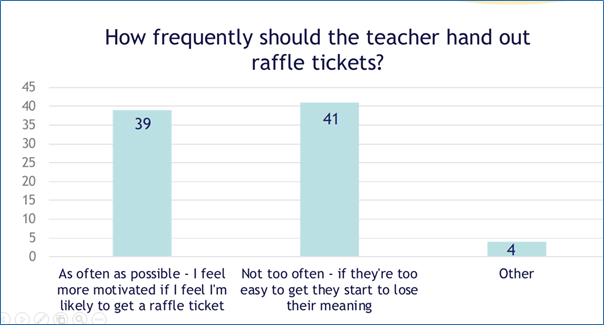

However, when students were asked how frequently they thought teachers should use this system, responses were surprising. The hypothesis was that students would feel that less regular rewarding would be better because, according to the research, rewards lose effect if they become too regular and predictable. However, students were equally split in their opinions and many felt that they would prefer the opportunity to receive rewards as often as possible because it helps with their motivation.

Figure 9 students responses to a survey question

As a result, advice is for teachers to consider the needs of their class. If the aim of the system of praise and rewards is to motivate students to work hard throughout the lesson, then giving ample opportunities to receive praise and/or rewards seems to be the more effective method. However, if the aim is rather to encourage students to stretch and challenge themselves, then it would likely be better to only reward students when they have done something particularly impressive so that the rewards do not become predictable and meaningless and students feel the need to strive to receive them.

While this was trialled with a raffle ticket system, it is likely that these findings would also apply to other systems of praise and reward, which is an area for further investigation.

Feedback from students

- “I think we should get raffle tickets any time we contribute or work above average.”

- “I think they should be given out often enough that they’re available but not too easy or everyone gets them.”

- “I like the idea that I can win something.”

- “I like to be able to choose my prize.”

What do you think are the next steps in order to develop this aspect of learning and teaching in the school?

In order to develop praise further in school it is important that continued emphasis is put on the nominations system so that teachers are reminded of how easy it is to use nominations as their own system of praise. In addition, teachers should continue to reflect on how they can make praise more meaningful to students; this should include making efforts to provide praise in a separate manner from how they provide targets for improvement when assessing work, but also considering what they do within lessons: their use of verbal praise, the system they have for praising students and how frequently and/or predictably they reward positive behaviour.

Something to take away: top tips for teachers aiming to develop their use of praise

- For maximum impact, make sure praise is ‘spontaneous’ or attempt to replicate that feeling by making it as meaningful as possible through student involvement or careful wording.

- Consider ways you can separate praise from feedback and targets.

- Use classroom rewards systems so that all students have access to praise but bear in mind that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach.

References

Center on Education Policy (2012) Student Motivation— An Overlooked Piece of School Reform (Washington DC: CEP)

Didau, and Rose, Nick (2016) What Every Teacher Needs to Know About Psychology (Woodbridge: John Catt Education Ltd)

Dweck, Carol S. (2007) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success (New York: Ballantine Books)

Lepper, M. R., Greene, D., & Nisbett, R. E. (1973) ‘Undermining children’s intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the “overjustification” hypothesis’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 28(1), 129-137.

Willingham, Daniel T. (2006) How Praise can Motivate – or Stifle (Washington DC: American Educator)